A temple for all the gods

From imperial Rome to Renaissance burials, the Pantheon has witnessed 2,000 years of history.

Table of Contents

From Agrippa's temple to Hadrian's vision

The first Pantheon was built by Marcus Agrippa around 27 BCE as a temple dedicated to all the gods of Rome. That original structure burned down in 80 CE, and again after a lightning strike in 110 CE.

Emperor Hadrian rebuilt it entirely between 118 and 128 CE, creating the rotunda and dome we see today. Curiously, Hadrian kept Agrippa's name on the pediment, honoring the site's origins while crafting a radically new vision.

Hadrian's revolutionary design

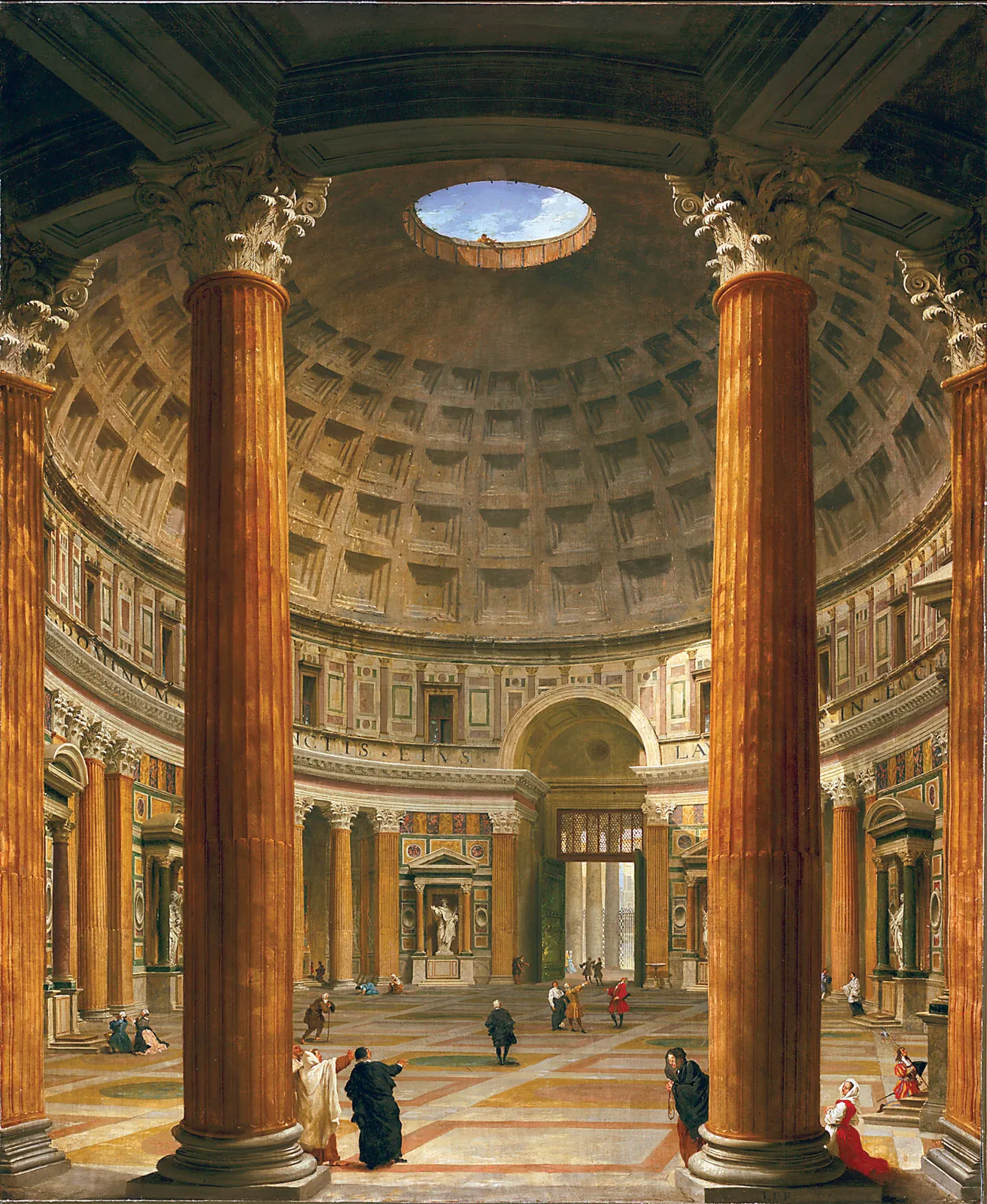

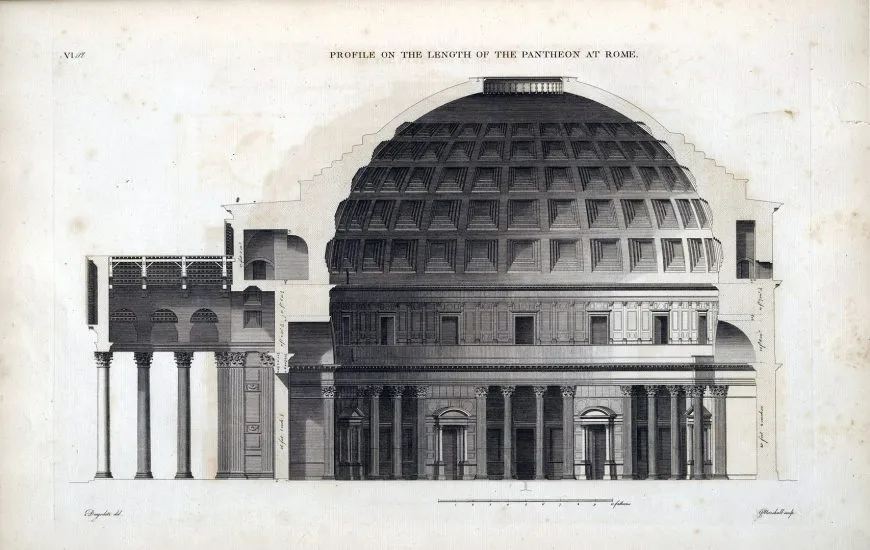

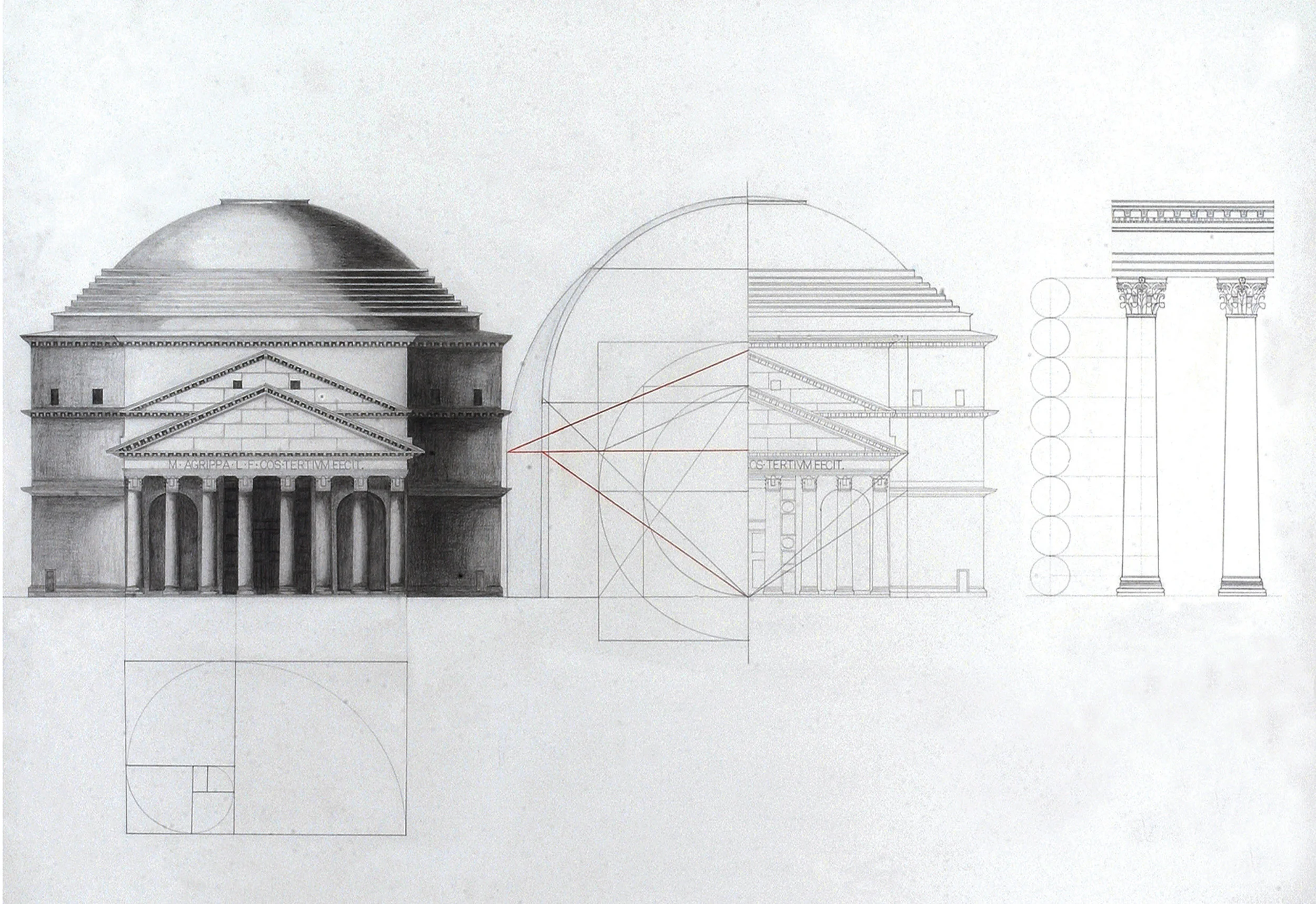

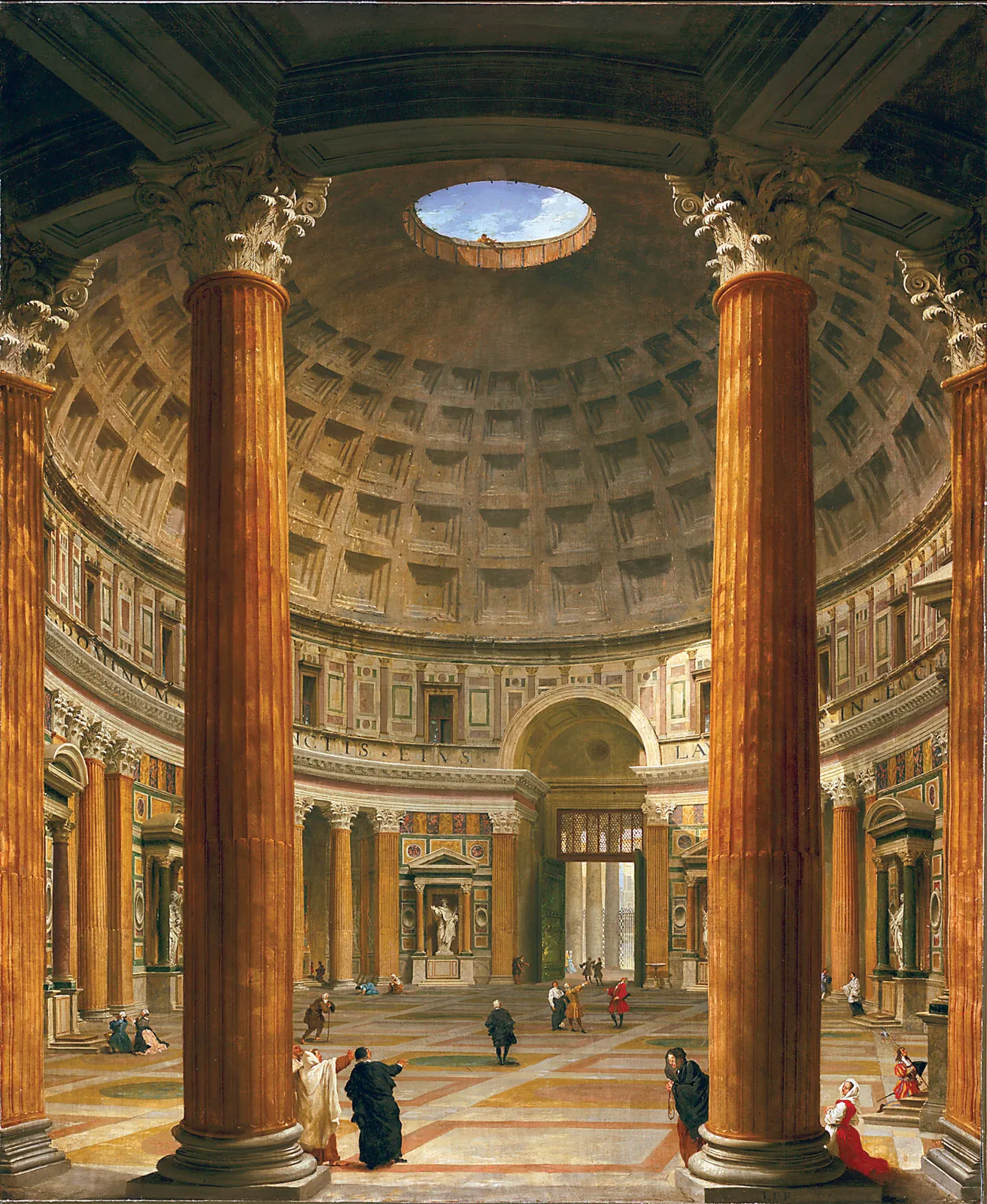

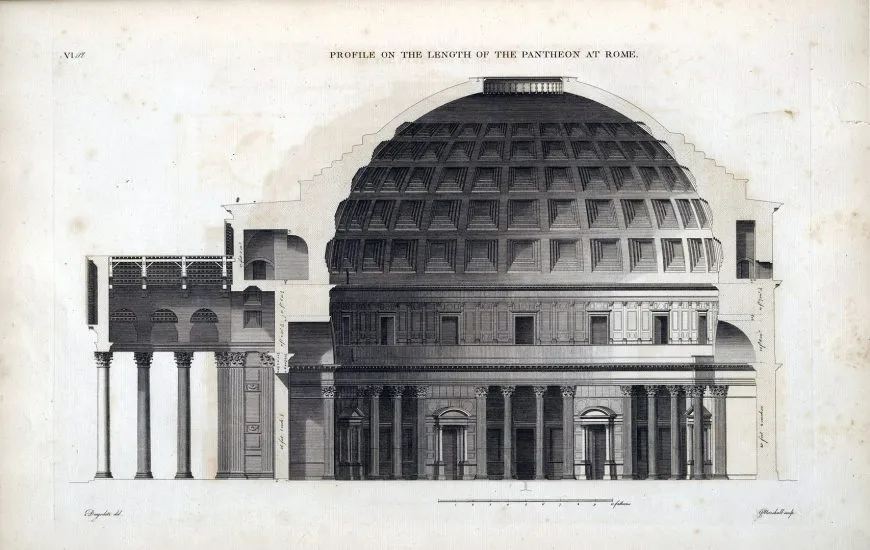

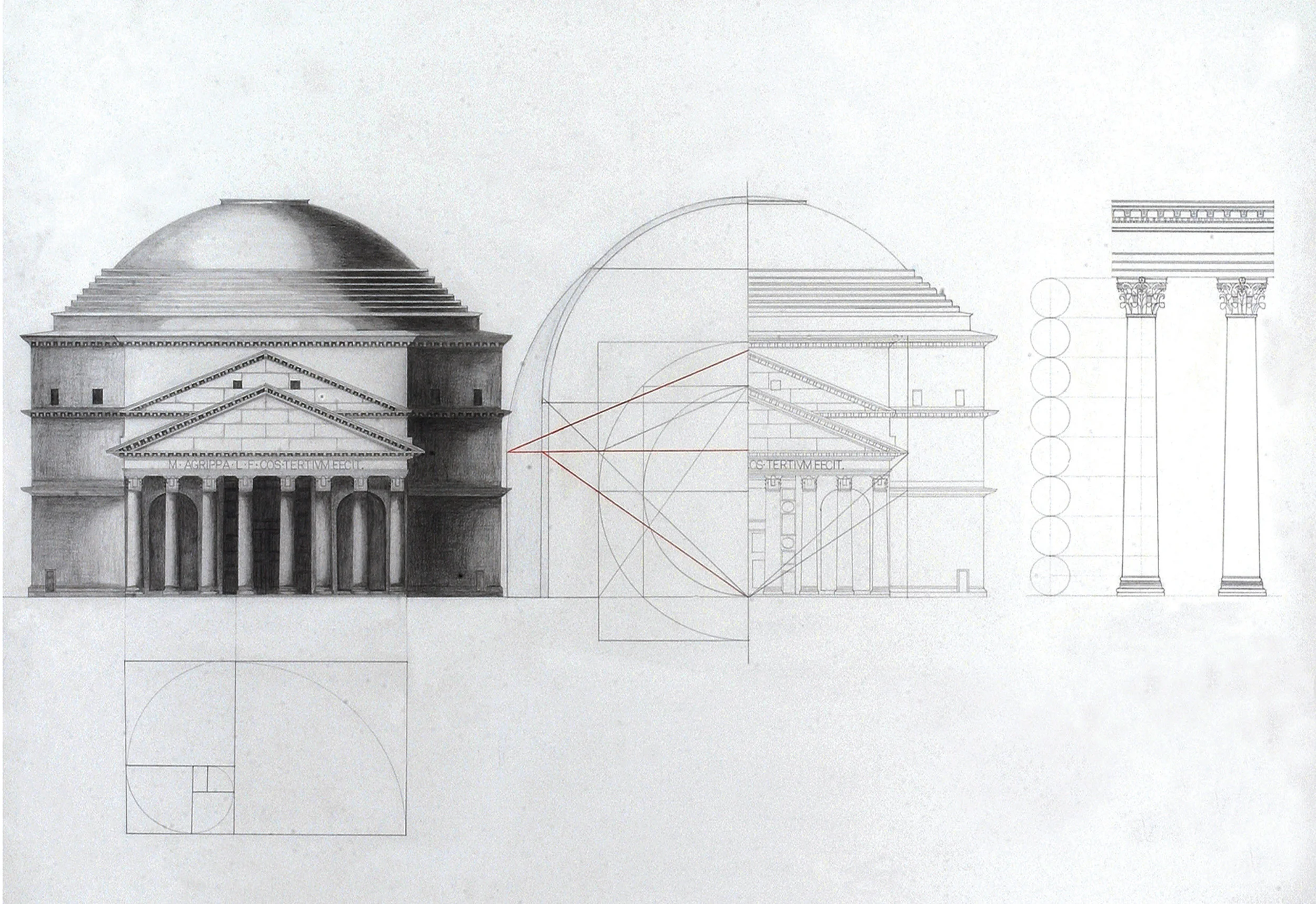

The Pantheon's design is a perfect sphere: the height from floor to oculus equals the diameter of the rotunda — 43.3 meters. This geometry creates a sense of cosmic harmony, a meeting place of earth and sky.

Massive Corinthian columns frame the porch, while the thick walls of the rotunda — up to 6 meters deep — support the dome's immense weight. Hidden arches and carefully graded concrete distribute stress across the structure.

The oculus: sky and spirit

The 9‑meter oculus at the dome's center is the only source of natural light. Sunlight moves across the interior as the day progresses, creating a constantly shifting interplay of light, shadow and space.

Rain falls through the opening onto the ancient marble floor, which slopes gently toward hidden drains. The oculus symbolizes the divine eye, connecting worshippers directly with the heavens above.

Roman concrete and engineering genius

Roman builders used innovative concrete — lighter aggregates near the top, heavier stone at the base. The dome's five rings of coffers reduce weight while maintaining strength, a solution that has held for nearly two millennia.

No steel, no modern supports — just volcanic ash, lime and brilliant design. The Pantheon remains the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built, outlasting countless later attempts.

From pagan temple to Christian church

In 609 CE, Byzantine Emperor Phocas gave the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV, who consecrated it as the church of Santa Maria ad Martyres. This transformation saved the building from the looting and destruction suffered by other Roman temples.

Christian use meant continuous maintenance, repairs and adaptations — adding altars, removing statues, installing tombs. The Pantheon became both a monument and a living place of worship.

Renaissance burials and royal tombs

In 1520, the great Renaissance painter Raphael was buried here, a rare honor that reflected his genius and status. His simple tomb, inscribed with a Latin epitaph, draws visitors from around the world.

After Italian unification, the Pantheon became the burial place of Italy's kings: Vittorio Emanuele II, Umberto I and Queen Margherita. Their tombs blend national symbolism with ancient grandeur.

The bronze ceiling and papal changes

In the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII removed the bronze ceiling from the porch to cast cannons for Castel Sant'Angelo and make the baldachin for St. Peter's Basilica. Romans joked: 'What the barbarians didn't do, the Barberini did.'

Despite changes, the essential structure and spirit of the Pantheon remained intact. Each era left its mark — frescoes, altars, plaques — without destroying the harmony Hadrian built.

Visiting through the centuries

Pilgrims, scholars and artists have visited the Pantheon for centuries, sketching the dome, measuring proportions and marveling at its survival. Renaissance architects studied it to unlock the secrets of Roman engineering.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Grand Tourists made it a must‑see stop. Writers like Stendhal and Goethe described the awe of stepping inside — a feeling that persists today.

Conservation and modern care

Modern conservation focuses on cleaning the marble, stabilizing the structure and managing visitor flow. Careful monitoring ensures the ancient concrete dome remains sound despite pollution, weathering and millions of annual visitors.

Recent projects have improved drainage, restored the bronze doors and upgraded lighting to enhance the oculus effect while protecting fragile surfaces.

The Pantheon in art and culture

The Pantheon has inspired architects from Brunelleschi to Thomas Jefferson; its dome influenced St. Peter's, the US Capitol and countless neoclassical buildings worldwide.

Painters, poets and filmmakers return again and again to its perfect geometry and haunting light. It appears in Renaissance frescoes, Romantic engravings and Hollywood films as a symbol of timeless beauty.

Piazza della Rotonda today

Piazza della Rotonda buzzes with life — cafés spill onto cobblestones, street artists perform, tourists gather around Giacomo della Porta's fountain. The contrast between the lively piazza and the serene interior adds to the experience.

Outdoor tables offer a front‑row seat to watch light shift across the portico, while gelato vendors and souvenir stands keep the atmosphere friendly and accessible.

Exploring the neighborhood

Just steps away, discover Piazza Navona with Bernini's fountains, the historic cafés of Via della Rotonda, and the quiet church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva with its Michelangelo sculpture.

For a deeper Roman experience, wander east toward the Trevi Fountain, south to Campo de' Fiori, or north into the boutiques and trattorias of the medieval quarter.

An icon of eternal Rome

The Pantheon embodies Rome's genius: practical engineering, aesthetic perfection and the ability to adapt and endure. It has outlasted empires, survived wars and remained continuously in use for nearly 2,000 years.

Today it stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site within the Historic Centre of Rome — a living monument where ancient grandeur meets everyday life, inspiring wonder in everyone who steps through its massive bronze doors.

Table of Contents

From Agrippa's temple to Hadrian's vision

The first Pantheon was built by Marcus Agrippa around 27 BCE as a temple dedicated to all the gods of Rome. That original structure burned down in 80 CE, and again after a lightning strike in 110 CE.

Emperor Hadrian rebuilt it entirely between 118 and 128 CE, creating the rotunda and dome we see today. Curiously, Hadrian kept Agrippa's name on the pediment, honoring the site's origins while crafting a radically new vision.

Hadrian's revolutionary design

The Pantheon's design is a perfect sphere: the height from floor to oculus equals the diameter of the rotunda — 43.3 meters. This geometry creates a sense of cosmic harmony, a meeting place of earth and sky.

Massive Corinthian columns frame the porch, while the thick walls of the rotunda — up to 6 meters deep — support the dome's immense weight. Hidden arches and carefully graded concrete distribute stress across the structure.

The oculus: sky and spirit

The 9‑meter oculus at the dome's center is the only source of natural light. Sunlight moves across the interior as the day progresses, creating a constantly shifting interplay of light, shadow and space.

Rain falls through the opening onto the ancient marble floor, which slopes gently toward hidden drains. The oculus symbolizes the divine eye, connecting worshippers directly with the heavens above.

Roman concrete and engineering genius

Roman builders used innovative concrete — lighter aggregates near the top, heavier stone at the base. The dome's five rings of coffers reduce weight while maintaining strength, a solution that has held for nearly two millennia.

No steel, no modern supports — just volcanic ash, lime and brilliant design. The Pantheon remains the largest unreinforced concrete dome ever built, outlasting countless later attempts.

From pagan temple to Christian church

In 609 CE, Byzantine Emperor Phocas gave the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV, who consecrated it as the church of Santa Maria ad Martyres. This transformation saved the building from the looting and destruction suffered by other Roman temples.

Christian use meant continuous maintenance, repairs and adaptations — adding altars, removing statues, installing tombs. The Pantheon became both a monument and a living place of worship.

Renaissance burials and royal tombs

In 1520, the great Renaissance painter Raphael was buried here, a rare honor that reflected his genius and status. His simple tomb, inscribed with a Latin epitaph, draws visitors from around the world.

After Italian unification, the Pantheon became the burial place of Italy's kings: Vittorio Emanuele II, Umberto I and Queen Margherita. Their tombs blend national symbolism with ancient grandeur.

The bronze ceiling and papal changes

In the 17th century, Pope Urban VIII removed the bronze ceiling from the porch to cast cannons for Castel Sant'Angelo and make the baldachin for St. Peter's Basilica. Romans joked: 'What the barbarians didn't do, the Barberini did.'

Despite changes, the essential structure and spirit of the Pantheon remained intact. Each era left its mark — frescoes, altars, plaques — without destroying the harmony Hadrian built.

Visiting through the centuries

Pilgrims, scholars and artists have visited the Pantheon for centuries, sketching the dome, measuring proportions and marveling at its survival. Renaissance architects studied it to unlock the secrets of Roman engineering.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Grand Tourists made it a must‑see stop. Writers like Stendhal and Goethe described the awe of stepping inside — a feeling that persists today.

Conservation and modern care

Modern conservation focuses on cleaning the marble, stabilizing the structure and managing visitor flow. Careful monitoring ensures the ancient concrete dome remains sound despite pollution, weathering and millions of annual visitors.

Recent projects have improved drainage, restored the bronze doors and upgraded lighting to enhance the oculus effect while protecting fragile surfaces.

The Pantheon in art and culture

The Pantheon has inspired architects from Brunelleschi to Thomas Jefferson; its dome influenced St. Peter's, the US Capitol and countless neoclassical buildings worldwide.

Painters, poets and filmmakers return again and again to its perfect geometry and haunting light. It appears in Renaissance frescoes, Romantic engravings and Hollywood films as a symbol of timeless beauty.

Piazza della Rotonda today

Piazza della Rotonda buzzes with life — cafés spill onto cobblestones, street artists perform, tourists gather around Giacomo della Porta's fountain. The contrast between the lively piazza and the serene interior adds to the experience.

Outdoor tables offer a front‑row seat to watch light shift across the portico, while gelato vendors and souvenir stands keep the atmosphere friendly and accessible.

Exploring the neighborhood

Just steps away, discover Piazza Navona with Bernini's fountains, the historic cafés of Via della Rotonda, and the quiet church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva with its Michelangelo sculpture.

For a deeper Roman experience, wander east toward the Trevi Fountain, south to Campo de' Fiori, or north into the boutiques and trattorias of the medieval quarter.

An icon of eternal Rome

The Pantheon embodies Rome's genius: practical engineering, aesthetic perfection and the ability to adapt and endure. It has outlasted empires, survived wars and remained continuously in use for nearly 2,000 years.

Today it stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site within the Historic Centre of Rome — a living monument where ancient grandeur meets everyday life, inspiring wonder in everyone who steps through its massive bronze doors.